Recreating the classic game of Sudoku in JavaScript, Python, and Rust

Show Table of Contents

📝 TLDR: I built a Sudoku game, you can try it out here 🕹️

Preface

The game of Sudoku is relatively new. In its current form, Sudoku took shape in the late 1970s. It was originally called "Number Place" and was first published in Dell Pencil Puzzles and Word Games magazine in 1979 by Howard Garns. In the mid 1980s, the game was introduced in Japan by the name "Sudoku" which means "single number" in Japanese.

In short, Sudoku is a logic-based, combinatorial number-placement puzzle. The objective is to fill a 9x9 grid with digits so that each column, each row, and each of the nine 3x3 subgrids that compose the grid contain all of the digits from 1 to 9. It is a fun and challenging game that usually does not last very long and can be played on a piece of paper or on a computer.

In this blog post, I will show you how to create a simple Sudoku game in three different programming languages: JavaScript, Python, and Rust. The goal is to demonstrate how the same game can be implemented in different languages and to show the differences in syntax and structure between them. Sudoku being a simple game, it is a great example to compare the three languages.

Rules

In a nutshell, Sudoku is a 9x9 grid (i.e. 9 3x3 subgrids) where each cell can contain a number from 1 to 9. The game starts with a partially filled grid and the player must fill in the remaining cells so that each row, column, and 3x3 subgrid contains all the numbers from 1 to 9 (i.e. no duplicates).

Design

To represent the Sudoku board, I decided to go with a simple 1-dimensional array of length 81. Each cell in the grid is represented by an index in the array. The top-left cell is index 0 and the bottom-right cell is index 80. The value of each cell is a number from 0 to 9, where 0 represents an empty cell. The game is won when the board is completely filled and all the rules are satisfied.

💡 Optimisation: The 3 diagonal 3x3 subgrids can be filled completely randomly (making sure that each digit appears exactly once in each subgrid) since they don't affect the rules of the game. The 54 cells can be solved using a backtracking algorithm.

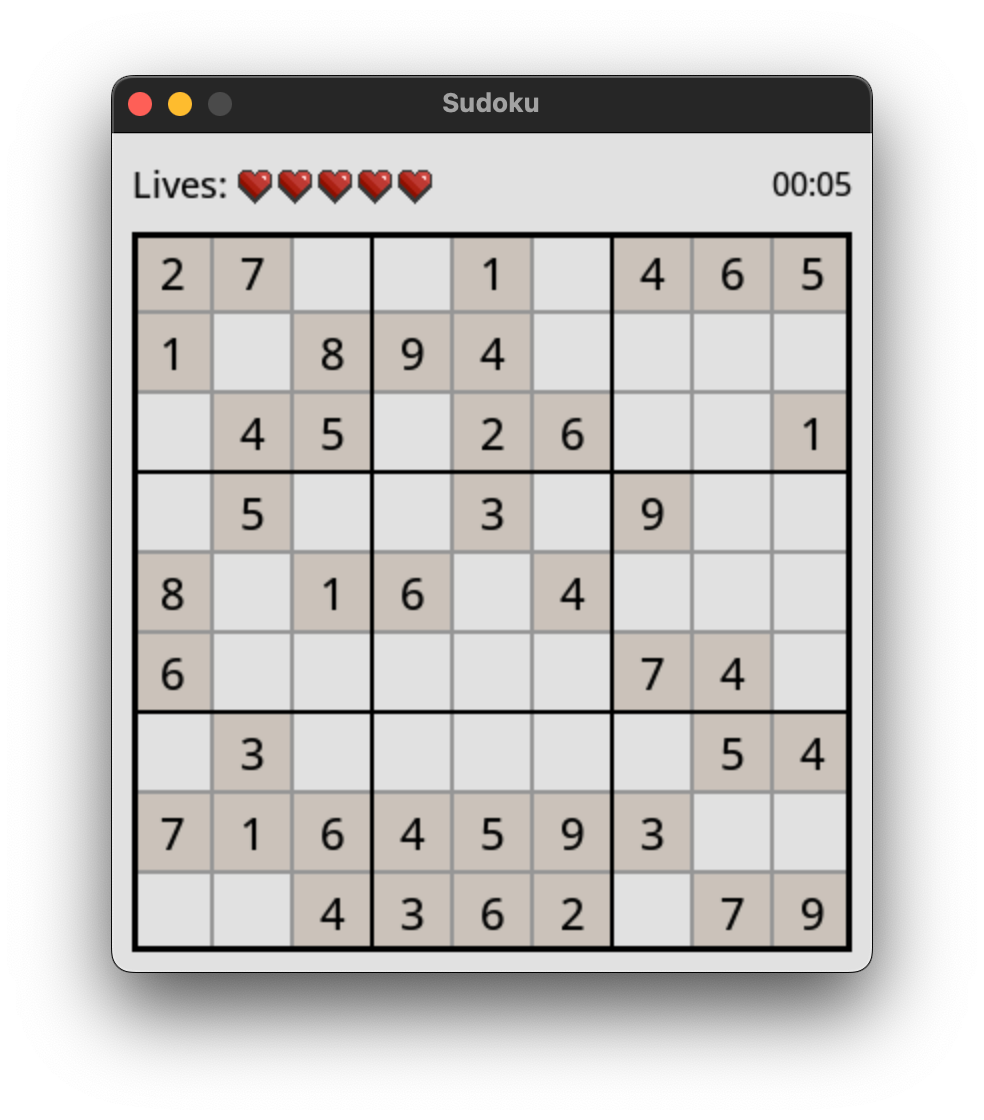

To fill in the remaining 54 cells, we can make use of a Depth-first search (DFS1) algorithm. In essence, we randomly fill the remaining board, one cell at a time until all the rules are satisfied. For example, say we are trying to fill cell at position (7, 8) (in the form (row, column) with zero-based indexing2) as seen in the following figure below. With the current state of the board, this cell has the following constraints (digits that cannot be placed in this cell):

- Row:

[3, 6, 9] - Column:

[1] - Subgrid:

[1, 6, 9]

The allowed digits for this cell are thus: [2, 4, 5, 7, 8]. We can then randomly choose one of these digits and continue filling the board until all the cells are filled. Eventually, we will reach a point where the board is completely filled and all the rules are satisfied. Although in this example this cell can be inferred directly just by looking at the positions of other 5 cells in the board. Since this subgrid is missing a 5, and two rows and one column each contain a 5, the only possible digit for this cell is 5.

How to fill a cell in a Sudoku board.

As you may have noticed, what we are doing is essentially a brute-force search. We are trying all possible combinations of digits until we find the correct one. This is a very inefficient way of solving the problem, but it is guaranteed to find a solution if one exists. In practice, this algorithm is very fast and can solve a Sudoku board in a fraction of a second.

Implementation

The implementation of the game is quite simple. We need to define a few functions to help us fill the board and check if the board is valid. The main function fill is a recursive function that fills the board one cell at a time. Each implementation has a slightly different structure, but the logic remains the same. For each cell, we get the allowed digits and try each one until we find a solution. If we reach a cell where there are no allowed digits, we backtrack and try a different digit in the previous cell.

JavaScript

In JavaScript, we define the fill function as follows. The function takes a 1-dimensional array of length 81 as input and fills the board in place. The function getAllowed returns an array of allowed digits for a given cell. The function fill is a recursive function that fills the board one cell at a time. If the board is filled completely, the function returns true, otherwise it returns false. JavaScript's syntax is simple and easy to read, albeit a bit verbose.

function fill(grid) {

for (let row = 0; row < 9; row++) {

for (let col = 0; col < 9; col++) {

if (grid[row * 9 + col] == 0) {

let allowed = getAllowed(row, col, grid);

for (let i = 0; i < allowed.length; i++) {

grid[row * 9 + col] = allowed[i];

if (fill(grid)) {

return true;

} else {

grid[row * 9 + col] = 0;

}

}

return false;

}

}

}

return true;

}

Python

In Python, we define the fill function as follows. The function fills the board in place. The function get_allowed returns a set of allowed digits for a given cell. If the board is filled completely, the function returns True, otherwise it returns False. If no digit is allowed for a given cell, the function backtracks and tries a different digit in the previous cell, resetting the current cell to 0. Python's syntax is concise and easy to read, making it a great language for writing clean and readable code.

def fill(self) -> bool:

for row in range(9):

for col in range(9):

if self.is_empty(row, col):

for digit in self.get_allowed(row, col):

self.grid[row, col] = digit

if self.fill():

return True

self.grid[row, col] = 0

return False

return True

Rust

Lastly, here's the implementation in Rust. The function fill takes a mutable reference to a 1-dimensional array of length 81 and fills the board in place. The function get_allowed returns a vector of allowed digits for a given cell. If the board is filled completely, the function returns true, otherwise it returns false. Rust's syntax is more verbose than Python but less verbose than JavaScript for this example. Rust's syntax is also more strict and requires more explicit type annotations, requiring more effort to write but resulting in more robust code.

fn fill(grid: &mut [u8; 81]) -> bool {

for i in 0..81 {

if grid[i] == 0 {

let allowed: Vec<u8> = get_allowed(&grid, i / 9, i % 9);

for digit in allowed {

grid[i] = digit;

fill(grid);

if fill(grid) {

return true;

}

grid[i] = 0;

}

return false;

}

}

true

}

Outro

Building a Sudoku game from scratch was surprisingly easy and fun. The game is simple enough that it can be implemented in a few hours in all three languages. The game is also a great way to compare different programming languages and see how they differ in terms of syntax and structure. JavaScript, Python, and Rust are all great languages for building games, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses. Feel free to check out the code for each implementation and try the game for yourself!

For the nerds among us, here are the game libraries I used for each implementation:

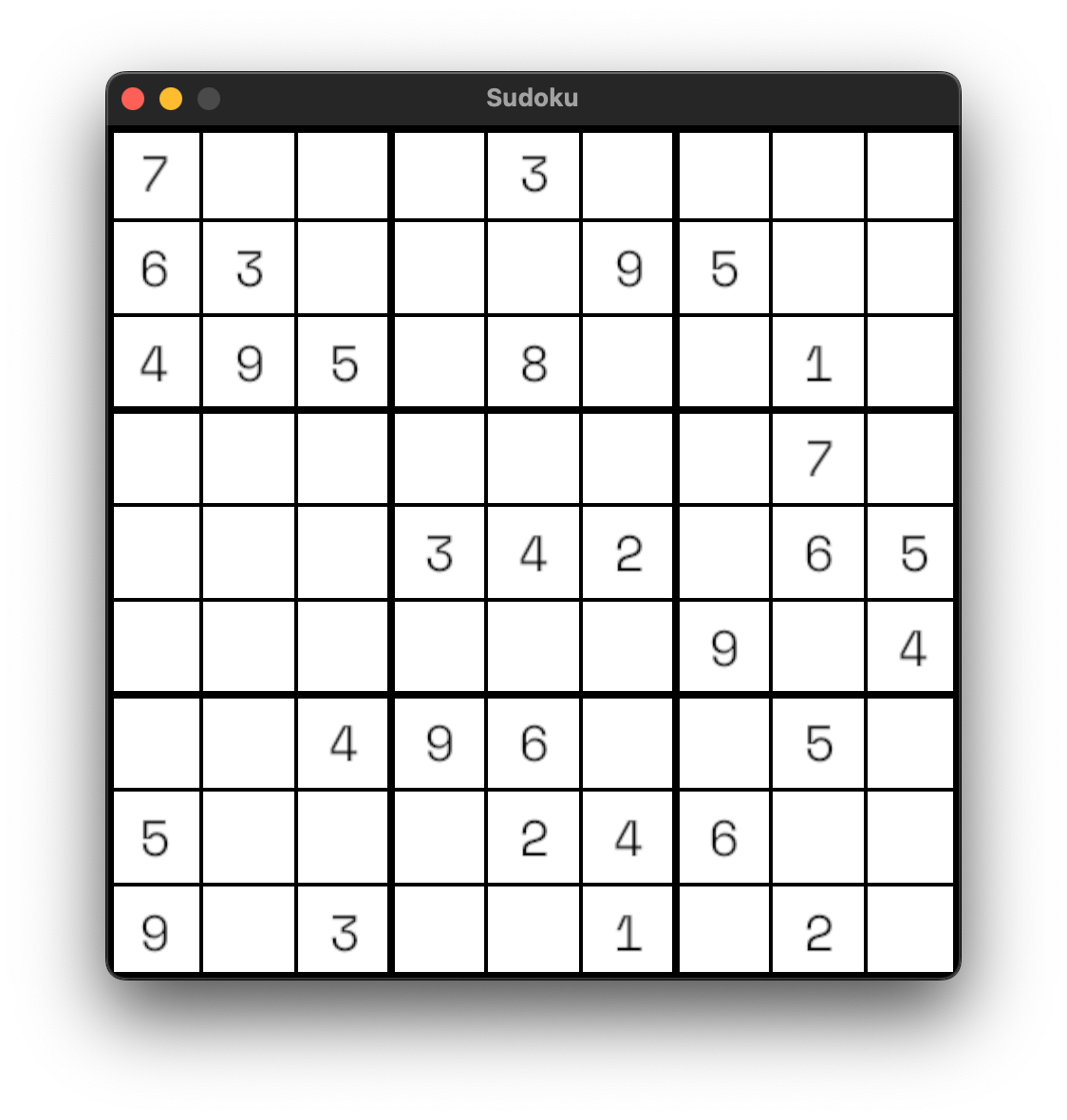

Sudoku in Python and Rust, from left to right.